The lettering from a Home and Colonial shop front, on display at Castle Drogo, and the coat of arms outside the inn at Drewsteignton .

In November 1882, William Slaughter’s sister Elizabeth married Reginald Drew ,older brother of Julius Drew,the co-founder of The Home and Colonial Stores which was later to become one of the most flourishing food retailing companies of that era. My mother remembers her great aunt Lizzie and her husband [known as Reggie]. Though described in the marriage settlement as a retired Naval Officer, Reggie later became a tea dealer and was involved in the family business. Far less dynamic and businesslike than his younger brother, my mother remembers Reggie as a charming man though with the reputation in the family as ‘something of a ne’er do well’ – no doubt in comparison with his very successful brother.When the Home and Colonial Stores was launched in 1888, William Slaughter was its chairman and remained so until he died in 1917.

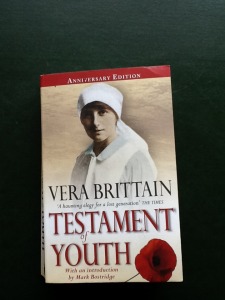

The Drew family had connections with tea importers and Julius had spent part of his early career in China as a tea buyer. When he returned, he set up as a tea merchant in Liverpool. The drinking of tea nationally had become ever more popular during the second half of the 19th century, and consumption per capita grew enormously making it a very profitable business. Drew went into partnership with a Liverpool butcher named John Musker, who had a wide knowledge of dealing in dairy products as well as meat. He was also astute in choosing suitable locations for the new shops. In 1888 there were 14 establishments, the main office being in the Edgware Road. By 1914 there were over 600 shops. The Home and Colonial brand, including the iconic black and gold lettering was meant to inspire confidence in the shopper and to imply the quality of goods and services on offer. Slaughter was closely involved in the expansion of this successful business from the start and the company was an important client of his law firm.

Julius Drew retired from business, while still under 40, and devoted himself to buying large rural properties and living the life of a country gentleman. He changed his name by deed poll to Drewe, hoping to establish a connection with Norman ancestry. In 1910 he purchased an estate at Drewsteignton in Devon where he commissioned the architect Lutyens to build him a castle. Castle Drogo, a vast imposing granite structure was never completed because of the advent of the first World War. Now belonging to the National Trust the castle and gardens are open to visitors who can enjoy the commanding views over the Teign valley from the site.

When Julius Drewe retired early from his active business ventures to enjoy the fruits of his labours, William Slaughter’s legal career was rapidly moving forwards. While at Ashworth, Morris and Crisp he had met a young trainee solicitor, William May who qualified in 1888. By the end of that year they had decided to go into business together. A joint bank account in their names was opened on the 1st January 1889, the official date of the beginning of their very successful partnership.

![Photograph of William Capel Slaughter [ca.1910]](https://writingfamilyhistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Wm-C-S-photo-225x300.jpg)